What does it mean to Not give up - For Entrepreneurs and Everyone Facing Adversity

The term "don't give up" is a motivational phrase that encourages perseverance and resilience in the face of challenges. It suggests that despite difficulties, setbacks, or failures, one should continue striving towards their goals and not lose hope. Quick note, we update these articles .. so this isnt the final form, but we try to do our best every iteration.

Key Interpretations:

-

Resilience: The phrase embodies the idea of resilience, emphasizing the importance of bouncing back after facing obstacles. It inspires individuals to maintain their effort and determination, even when the situation seems discouraging.

-

Motivation: It serves as a reminder to stay motivated, pushing through periods of doubt or frustration. This mindset can lead to personal growth and achievement, reinforcing the notion that success often requires persistence.

-

Support and Encouragement: "Don't give up" is frequently used in conversations to support others, conveying a sense of solidarity and encouragement. It reassures individuals that their struggles are acknowledged and that they are not alone in their efforts.

Contextual Usage:

- In personal development literature, this phrase is often linked to achieving long-term goals and the importance of tenacity.

- In sports and competitive environments, it signifies the spirit of continuing to fight for victory despite the odds.

- It's also prevalent in popular culture, such as songs and movies, where characters embody this spirit by overcoming significant challenges.

Related Templates

Lets explore a bit more, what happens within a person who is facing this feeling of giving up. When a person feels like giving up, they experience a cascade of cognitive and emotional responses that can profoundly impact their mental state. In psychology, this state is often analyzed through concepts related to learned helplessness, ego depletion, emotional exhaustion, and rumination. These factors help explain why the impulse to give up can feel so overwhelming.

Did you know that daily our soul continues to transforms, we embrace

1. Learned Helplessness and Learned Fortitude, and its a choice.

- Learned helplessness occurs when a person feels that they have no control over the outcomes of their actions, leading to a passive resignation in the face of adversity. This term, first explored by psychologist Martin Seligman, explains that when people repeatedly encounter failures or setbacks, they may begin to believe that effort is futile, resulting in feelings of powerlessness and a diminished drive to persist. People experiencing learned helplessness often have low self-efficacy—the belief in their ability to influence events—leading them to disengage from goals that once mattered to them.

2. Ego Depletion

- The concept of ego depletion suggests that self-control and willpower are finite resources that can be exhausted over time. According to this model, the mental effort required to stay focused and resist giving up can eventually wear down one's cognitive and emotional reserves. Roy Baumeister, a psychologist who has extensively researched ego depletion, found that when individuals are mentally or emotionally drained, their capacity to persist in challenging tasks diminishes. This depletion can lead to feelings of apathy, reduced motivation, and an inability to cope with even small challenges.

3. Emotional Exhaustion and Burnout

- Emotional exhaustion, a key component of burnout, is a state of feeling emotionally drained and depleted due to prolonged stress. It is frequently discussed in occupational and clinical psychology, where people who face ongoing pressures without sufficient recovery time start feeling detached and pessimistic. Emotional exhaustion can lead to depersonalization, where individuals feel disconnected from their own goals, identity, and motivations. Psychologists Christina Maslach and Susan Jackson describe this as a state where individuals feel "used up," struggling to muster energy for tasks that once brought satisfaction.

4. Rumination and Cognitive Distortion

- Rumination involves repeatedly thinking about distressing situations, which can trap individuals in a cycle of negative thoughts. When people ruminate, they often focus on their perceived failures and weaknesses, magnifying the reasons they believe they should give up. Cognitive distortions—such as catastrophizing (expecting the worst outcome) and personalization (blaming oneself disproportionately)—can also reinforce this negativity, creating a mental environment where giving up feels not only justified but inevitable. According to psychologist Susan Nolen-Hoeksema, rumination can intensify feelings of hopelessness and impede problem-solving, making it harder to envision a path forward.

5. The Role of Self-Compassion (or Lack Thereof)

- When a person lacks self-compassion, they are more likely to engage in self-criticism and doubt, which can accelerate the impulse to give up. Research by psychologist Kristin Neff emphasizes that self-compassion helps people cope with setbacks more resiliently. However, without it, people may fall into a harsh, self-judgmental mindset that exacerbates feelings of inadequacy and hopelessness.

Of these we would like to draw our attention to the factor of learned helpness and then later the process of learning and how to rig to block off bad behavioural transformation that makes one a giver uper.

Learned helplessness and lack of focus are interconnected in ways that can significantly impact motivation, productivity, and overall mental health.

-

Cycle of Reduced Motivation and Focus: Learned helplessness occurs when repeated failures or negative experiences lead someone to believe they have no control over outcomes, making them feel powerless and passive. This state often leads to a lack of motivation, as the person stops seeing value in efforts. In turn, when motivation drops, so does focus, as individuals may become less engaged with tasks, distracted, or even apathetic. So the 1 million dollar question is, is it ADHD or MDHD i.e. do we lack attention at irregular time intervals is the real enemy or the intrensic lack of motivation. You know neccessity if the mother of invention. What necessisity do we periodically not see as necessary and why. If we get good circulation, we will expound more. What do you think is it attention or motivation?

-

Cognitive Overload: The belief that "nothing will work" in learned helplessness often consumes cognitive energy, leaving less mental bandwidth for concentration. This rumination can lead to a lack of focus, as energy and attention get diverted away from the task at hand toward internalized worries or doubts. So is this the answer to the Why we come to believe and how easily we are willing to believe something, and does that make us successitble to behaving in unstable, unresolute, unpresistent way in order not conducive to create an enduring advantage. Heres a question, how long are you taking to learn a bad behavior, and how you can create what we call a intervention barrier. We are building an enduring advantage with respect to our competition and challenges anyone would face to operate a business with consistency. Point to note is that the notion on consistency does not include the vocabulary of giving up. However, we will nail that in at another time.

-

Behavioral Avoidance and Inattention: With learned helplessness, people are likely to avoid challenging tasks because of the belief that they’ll fail, making it harder to focus on work and goals. This avoidance behavior reinforces a lack of concentration and can increase procrastination.

-

Anxiety and Focus: When someone feels helpless, anxiety often increases, and anxious thoughts can distract and fragment focus. Persistent anxiety from learned helplessness can cause a cycle of worry that further diminishes concentration and engagement.

Breaking this cycle often requires targeted interventions, like setting small, achievable goals to rebuild a sense of control and incorporating practices to manage focus and reduce distractions.

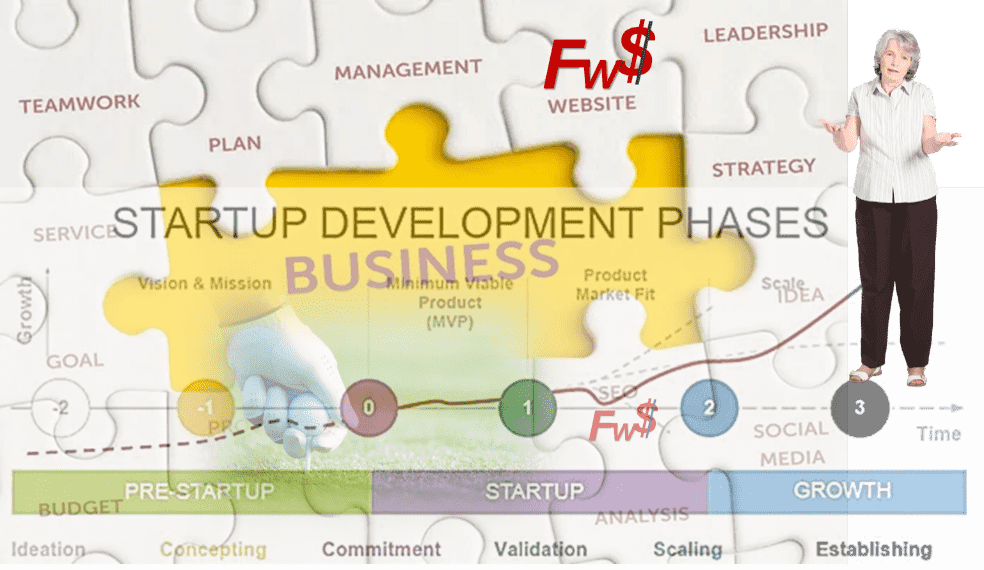

As mentioned before, creating an intervention barrier to break the habbit potential before it forms requires to have 4 dimentional view of the circumstance beyond a lateral timeline view and a vertical timline of time itself.

The number of repetitions required to learn a behavior can vary greatly depending on the complexity of the behavior, individual learning ability, the context, and reinforcement consistency. However, researchers have proposed some general guidelines and findings based on different studies and types of learning.

1. 21-Day Rule vs. 66-Day Rule

- The “21-day rule,” popularized by Dr. Maxwell Maltz in the 1960s, suggested that it takes about 21 days to form a habit. However, recent studies indicate that this figure is often too simplistic.

- A 2009 study by Dr. Phillippa Lally and her team at University College London found that it took an average of 66 days for participants to form a habit, though the exact time ranged from 18 to 254 days depending on the complexity of the habit The Power of Repetition in Behavioral Learning

- In motor learning, for example, some researchers suggest that 300 to 500 repetitions are necessary to develop a basic skill, while around 3,000 to 5,000 repetitions might be needed to refine a skill to an automatic level, especially in fields like sports and music.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) research emphasizes “overlearning” through repetition to make new behavior patterns automatic and replace old habits. Here, the number of repetitions required can vary widely based on individual differences and the behavior’s complexity .

3. Elasticity and Reinforcement

- Neuroplasticity research shows that creating and strengthening neural pathways requires consistent practice and reinforcement. The Hebbian theory ("cells that fire together wire together") explains that repeating behavior increases neural connections, eventually making behaviors more automatic. For lasting neural changes, some experts suggest at least 10,000 hours of practice, though this number often relates to mastery rather than basic learning .

4. Individuality

- Individual factors such as motivation, learning style, and environment significantly impact how quickly a person learns a behavior. For instance, highly motivated individuals may require fewer repetitions to learn and maintain a new behavior because of stronger reinforcement associations.

In conclusion, learning a behavior typically requires between 20 to 100 repetitions for simpler habits but may range to hundreds or thousands for complex skills. Making a behavior automatic or habitual often requires ongoing reinforcement, with estimates ranging from 66 days for basic habits to years for expertise-level skills. Where do you know that you fall into, if we were to break the frequency range into blocks of 10 i.e., do you get sometime internalized after 20 reps, or 30 reps, and so on. Your answer would be much higher for conceptual term of "give up", since it has multiple layers. There is an inner agency aspect in this than just the act of moving in a particular direction, to work more effectively and consistently operate a business, or be an athlete of repute, or a scientist or simply being able to keep up with the daily demands of social and civil life.

Here’s the list of strategies to intervene before a habit is formed, supported by research and specific study details where available.

1. Increase Awareness (Mindfulness)

- Practicing mindfulness can help individuals notice thoughts, emotions, and urges before they act on them. Mindfulness practice is shown to decrease habitual behaviors by creating a pause between trigger and response, making it easier to choose a different behavior. A 2010 study conducted at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) found that an 8-week mindfulness course reduced stress-related eating in participants by 25% on average, helping prevent stress-induced eating habits from forming

2. Identify and Modify Triggers

- Habits are often linked to specific environmental or emotional triggers. Modifying or removing these triggers can disrupt the habit loop. Research from the University of Washington in 2017 demonstrated that removing or substituting triggers for habitual behaviors (like reducing screen time) significantly decreased engagement with unwanted activities in 73% of participants. By creating new associations, individuals can prevent the original habit from solidifying .

3. Pre-commitment Strategies

- Pre-commitment makes it harder to engage in an unwanted behavior by creating external barriers. A 2014 study at the University of Cambridge found that people who used “commitment devices” (such as time-locking apps on their phones) decreased social media usage by 45% on average over a month. This concept, known as “choice architecture,” prevents impulse behavior by manipulating the environment .

4. Delay one Routine

- Delaying gratification or replacing an old routine with a new one can help rewire behavior. In 2018, research at Columbia University found that individuals who practiced a 10-minute delay technique to resist unhealthy snacking were able to reduce consumption by 20%. Replacing old routines with healthier choices also formed stronger new habits in 61% of participants within a 4-week period .

5. Use Self-Monitoring

- Self-monitoring involves tracking when, where, and why behaviors occur. Studies show this can reduce automaticity. For example, research at the University of Oxford in 2021 revealed that participants who tracked their screen time reduced usage by 30% within two weeks. Self-monitoring helps individuals recognize patterns, interrupt habit loops, and implement changes more effectively .

6. Visualize Long-Term Consequences

- Focusing on the long-term negative consequences of a habit can counteract the immediate reward bias. A 2019 study at the University of Michigan demonstrated that smokers who visualized the long-term health impacts of smoking were 25% more likely to resist cravings over a month. This form of visualization helps reinforce the delayed benefits of not engaging in certain behaviors .

7. Reward Small Wins

- Act Positive, reinforcement of small, desired behaviors can create new, healthier habit loops can go a long way. Research from Harvard University in 2015 found that participants who rewarded themselves for choosing healthy alternatives (like opting for water over soda) were twice as likely to repeat the behavior, showing that rewards can strengthen new habits and weaken the original unwanted behavior.